The High Cost of Free Incentive Parking

Wednesday, July 13th, 2016I have a confession to make: I think park’n’rides, or incentive parking as we call them in Montreal, are a bad idea.

Everybody seems to be asking for more and more incentive parking these days, and anyone questioning the driving component of our transit cocktail model may incur the anger of drivers and get painted as some sort of tofu-loving anti-car zealot. Well, I don’t like tofu, but I don’t like free park’n’rides either. Besides being bad for the city, they just don’t make economic sense.

Most people assume providing parking basically costs nothing for a transit agency. Plop a parking lot next to a train station, and you never have to think about it again. Just drive to the station and take the train.

Except, it turns out that parking is surprisingly expensive.

First, there is the one-time expense to buy the land and then to build the parking lot. Then, the parking lot requires a variety of operating expenses for things like maintenance (snow clearing, salting, cleaning, raod work…), security (lighting, cameras), and taxes, to name a few.

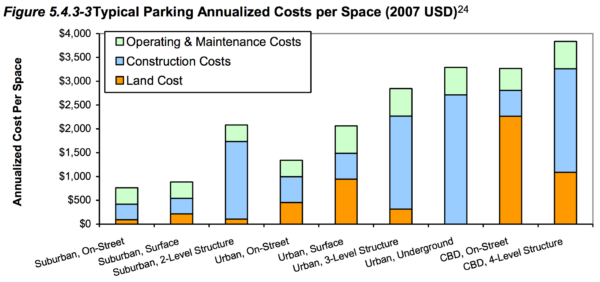

It’s not so easy to figure out what the exact cost is to provide free parking, broken down per user and per day. One good source is this 2016 study analyzing the total cost of providing parking, that is, land, construction and maintenance costs, in the US. The following graph shows the annualized costs for different types of parking spaces (note: land and construction costs are amortized over 20 years):

According to the study, surface parking lots typically costs around $1000 in the suburbs and $2000 in the city per year to provide. Those numbers were for 2007 and in US Dollars, so after adjusting for inflation (9 years, 15% total) and converting to CAD, that’s about 1500$-3000$ per year. Every year. For one single parking spot.

Another source, Calgary Transit estimated its 2011 parking costs to ~700$-1642$ per year (assuming 20 year amortization for a lot, and 40 year amortization for a parking structure).

Another survey of parking of American Transit agencies found the average operating cost for a total of 288,000 parking spots to be 1,100 USD per year, or about 1,425 CAD (see this spreadsheet). What’s interesting is that even though the transit agencies charge around 4.50$ per day on average for parking, on average they only recover 34% of the parking costs.

Now, consider that every commuter parking spot can pretty much be used by only one car every day. One person, who drives to the train in the morning and picks up the car after work in the evening. If we’re lucky, we may get up to 1.3 people per vehicle, which is the average occupancy rate of a car.

Moreover, in Montreal, the commuter rail parking lots of the AMT have an occupancy rate of 80%, but the unused 20% still has to be paid for.

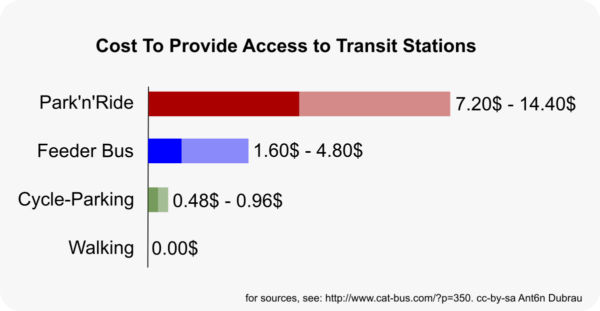

Overall, your typical free parking costs around $7.20 to $14.40 per weekday to provide, subsidized by the transit agency or the city.

| $ 1500 / 260 work days = $5.77 per day $ 5.77 / 0.80 occupancy = $7.21 per day |

$ 3000 / 260 work days = $11.54 $ 11.54 / 0.80 occupancy = $14.42 |

In terms of economic efficiency, this is quite a waste of money. Instead of having drivers go downtown and have them pay for their own parking, everybody has to pay for the drivers who park near a transit station, on top of having to subsidize the transit itself as well. If this is an ‘incentive’ that society provides to encourage transit use, we’re getting a pretty bad return on investment. Because the advantage of a few drivers being able to park near transit does not outweigh the money that we collectively spend to provide that parking.

If we look at cost per user, it is much more efficient to provide bicycle-parking in those same lots. It is possible to fit 15-20 bicycles in the space required for one parking spot in a parking lot. That’s because the lot is actually twice as big as the actual space required by a car: you need one car-area to put the car, and the equivalent of another car-area for the car to drive to the parking spot.

And walking to the station is even more economically efficient – it’s free.

Comparing with Feeder Buses

Of course it’s not realistic for everybody to just cycle to transit stations, and many don’t live within walking distance. So how else can we bring people to the trains?

The most popular alternative is to provide feeder buses, which collect passengers and bring them to the bus station. And despite requiring drivers and equipment, a feeder bus may actually be cheaper than parking!

Unfortunately, transit agencies don’t generally provide enough information that allows estimating how much it costs to provider feeder buses per person, so we can only infer from available numbers.

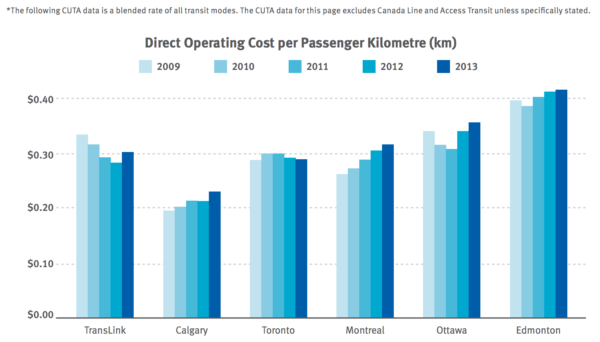

In 2014, Translink, Vancouver’s Transit Agency, published a report which contains a table of costs for operating transit per passenger-kilometer.

The chart shows blended operating costs, which is the overall operating cost for bus, metro, and rail combined, for several Canadian cities. We see from the graph that operating cost is lower in Calgary and higher in Ottawa and Edmonton. The difference is consistent with the transit model in every city: Calgary has an efficient light rail system, which is cheaper to operate than buses, because the vehicles are much larger, and most of their buses feed into the light rail. On the other hand, Edmonton and Ottawa have much smaller rail systems, and have to rely on the more expensive-to-operate buses.

According to this chart, Montreal’s transit operating cost was a little over $0.30 per passenger kilometre in 2013. Since this number does not take into account capital costs, we can adjust it up by about 20% (capital costs for buses is about 20% of operating costs) and round it up to $0.40 to account for the blending of different modes.

This means that bringing a person to a train station 2km away by bus costs about $1.60 per day (2 trips). Even if the person lives 6km away, this would only cost $4.80, which is still much less than providing parking, which costs $7 or more!

Note on distance: on the island of Montreal, only few people are farther than 6km away from a rail station, Commuter rail included (which is where most of the parking is). Even in the South Shore (Brossard and Longueuil), most are within 4km of the major transit terminals (Terminus Longueuil, Terminus Panama, Terminus Chevrier) and the commuter rail stations.

Overall we get the following cost estimates:

Alternative Use of the Space used for Parking

If you get more people to take buses from their homes, walk, or maybe even take a bicycle, you free up the land right next to the station. So instead of wasting valuable transit-adjacent land on parking the land can now be developed, to build apartment, commercial or office buildings and generate property taxes for the city, which in turn can be used to improve feeder buses. (The cities already pay most of the subsidies to operate transit).

People will want to live there, because they can quickly get downtown and businesses would want to locate there, because many people pass through the area. Transit stations would become the centers of little transit towns.

But also, you suddenly have people who don’t need to rely on either parking or feeder buses to get to the transit station – because they’re already right next to the station. Anybody who doesn’t need a bus or a parking spot to get to transit will be less expensive for the transit system as a whole.

Transit systems are based on cross-subsidies: some people pay more, so that others pay less. Short trip commuters subsidize those who go from one end of the line to the other. Metro users subsidize bus-&-metro users. The person who takes one ride pays the same as the person who uses a transfer.

And free incentive parking users should realize that they are benefitting from a premium service provided below cost – and provided to those who are more likely to be better off. In effect, those walking, cycling and even those taking buses are subsidizing the car owners who receive free parking.

When people complain about the lack incentive parking, remember that free parking is uneconomical. Money was invested in parking, when it could have been invested in service.

Space was allocated to parking, when it could have been developed to bring in tax revenue.

And maybe we should realize that parking at rail stations should not be free.

The following shows the comparison of two suburban transit stations, inside suburban towns of similar sizes that are in turn in metropolitan areas of similar size. One stop is immediately surrounded by parking, the other by a walkable town.

Above: Sainte-Therese (population 26K), 25km from downtown Montreal (pop 3.9M).

Below: Königs-Wusterhausen (pop 34K), 28km from downtown Berlin (pop 4.3M).

In Sainte-Therese, the rail station is close to the middle of town. But the parking is plenty and right next to the station, displacing the chance for a town centre. There are some condo-buildings around, but most of the area surrounding the station consists of low-density commercial buildings, most with more parking. There’s also a large bus terminus with 11 bays using up a lot of space as well. The terminus services thirteen lines.

By comparison, the Train Station in Königs-Wusterhausen is the center of a small town, with a pedestrian plaza, a mixed-use town-centre, plenty of bicycle parking, and bus stops served by a total of fifteen bus lines. Parking is still provided, because of increasing motorization levels, sprawl, and the resulting pressure to provide parking, but it’s pushed further away from the station, mostly to the far right.

The primary bus stop in Königs-Wusterhausen is small in area, because its primary purpose is to pick up and drop off passengers, not to store buses in the middle of a town. Image source.