Airport Trains Suck. Will REM Too?

Thursday, May 26th, 2016The Caisse’s REM proposal has given Montrealers hope to finally have a rail connection to the airport.

The problem with rail connectors to airports, however, is that they are generally not a very good use of money: they are often expensive and have low ridership. Airport connectors underperform.

Don’t get me wrong, I like the idea of taking a metro home from the airport. I think most people would love that too, which is why everyone is so excited about it. But even if everyone will use it at some point or another, most only go to the airport once or twice a year. Thus, on any given day, not many people will use it. And that means low ridership.

Comparison with airport connectors in other cities

How many people would use the new proposed airport connector? In their marketing material, the Caisse claims 10,000 people will use it every day. But they have refused to provide their ridership study to back up that claim.

Given that the airport express bus is currently used by about 3,000 people per day, is this increase in transit ridership credible? Or are they being overly optimistic?

Since the Caisse is not releasing their numbers, I made my own “studyâ€. Using a simple model, I have compared the ridership of North American airports with rail connections, to see what ridership could be like in Montreal. The assumption is that the proportion of people taking transit vs cabs or cars is similar across different airports. So if Montreal Trudeau is three times smaller than New York’s JFK, then the ridership of its transit line should be three times smaller as well.

To make results comparable to Montreal, the model includes airports with the following characteristics:

- they must be in North America, to have a similar relative use of cars and transit

- the rail connection must be the only major transit connection to the airport

- the rail connection must be frequent (every 15 minutes or better)

- the rail connection must provide a reasonable connection into town

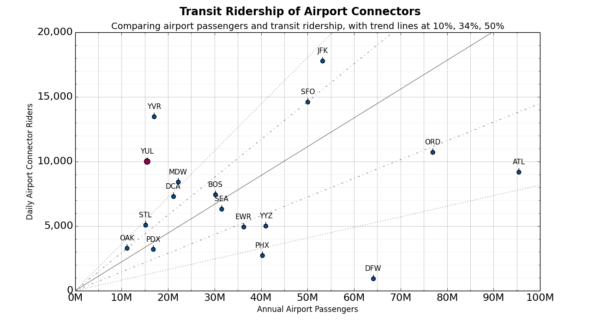

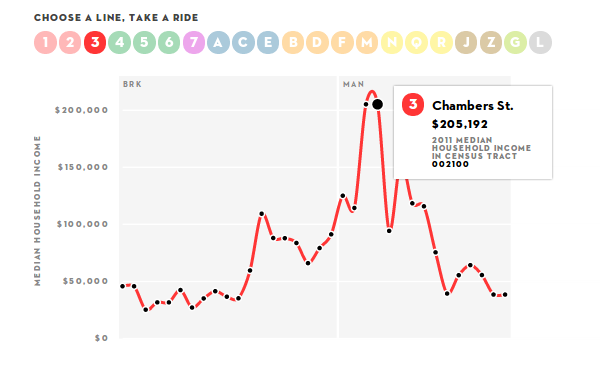

The scatterplot below shows daily ridership of the rail connector vs annual number of passengers through the airport (data). Airports in the upper left have a lot of transit ridership relative to their size, and airports in the bottom right are doing really badly. Note that large hub airports airports will be under-represented using this heuristic, because more passengers transfer to other flights at the airport.

We see, first of all, that some airport connectors really do suck. In a whole day, they could barely fill a couple of trains. Most airport other connectors do ok, and bring in about 3K to 5K riders for every 15M airport passengers per year (i.e. the size of Montreal’s airport).

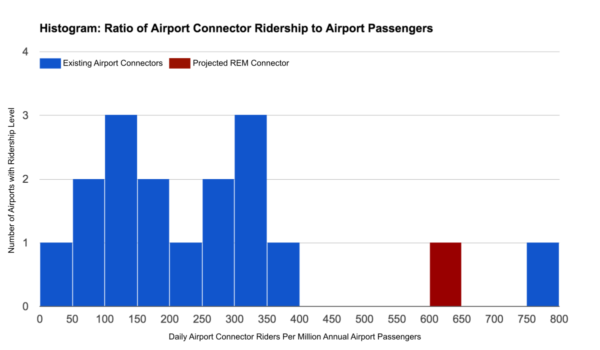

One airport does exceptionally well, and that’s Vancouver’s Canada Line. But it really is an outlier. It seems that the Caisse wants to create another such outlier with the REM, way beyond the 90% percentile. The ridership relative the total number of airport passengers for those two lines would be really far away from all other North American Airport connectors:

On the whole, their 10K estimate is not entirely outrageous, but leans on the optimistic side. Maybe a more conservative estimate (but still assuming we can do better than the average because transit use is generally higher in Montreal), would be 5,000 to 6,000 riders per day. Definitely one should be concerned that the Caisse is using too optimistic projections.

Lessons From Toronto

One airport-connector project that turned out to have overly optimistic projections is the Union Pearson Express in Toronto.

The Express was initially sold to the public with a projected ridership of 8,000/day during the opening year. After construction started, the number was revised down to 5,000 after the first year and only reaching 7,500/day by 2025!

And once it was built, the ridership was actually declining after a lethargic start, down to about 2,200 raiders per day, as most people were put off by the $27.50 fare. At that point the fare was slashed to $12 and ridership quickly increased to be in line with projections (~5000/day).

The Pearson Express was built at a cost of 456 million dollars. In absolute terms, this is pretty cheap for a transit line, and was made possible by running most of the Pearson Express on existing commuter rail tracks. However, considering that only 5000 people use it every day, that’s a cost of $91,200 per daily rider. In terms of cost/benefit, that turns out to be very expensive compared to other transit lines:

| construction cost(adjusted to 2013$) | weekday ridership | cost/rider | |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-Train (lrt) | 27M$ | 14K | 1901$ |

| C-Train (lrt) | 582M$ | 187K | 3110$ |

| Edmonton lrt | 404M$ | 70K | 5774$ |

| Pie-IX Busway (brt) | 316M$ | 70K | 4514$ |

| Laval Extension (metro) | 829M$ | 60K | 13825$ |

| Canada Line (light metro) | 2100M$ | 135K | 15441$ |

| Spadina Extension (metro) | 2400M$ | 100K | 24000$ |

| Pearson Express (heavy rail) | 456M$ | 5K | 91200$ |

Transit lines can have hundreds of thousands of users per day. In general, a line that can only accumulate 5000 to 10,000 thousand people per day is not really worth building as rapid transit. In fact, if such a line weren’t an airport connection, most would consider that it only deserves a frequent bus line, or maybe a streetcar.

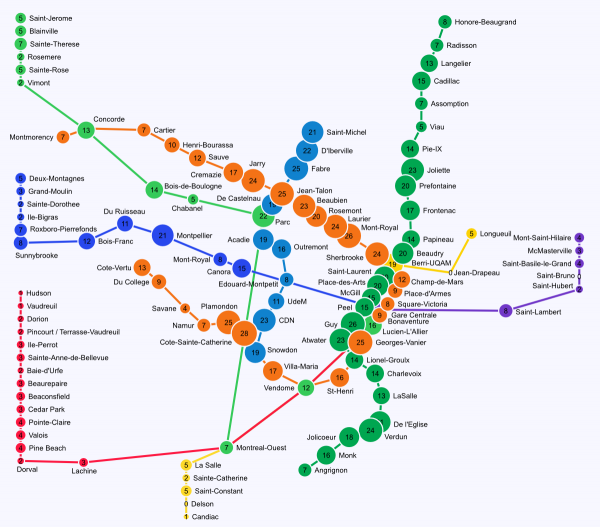

Comparing to the Metro

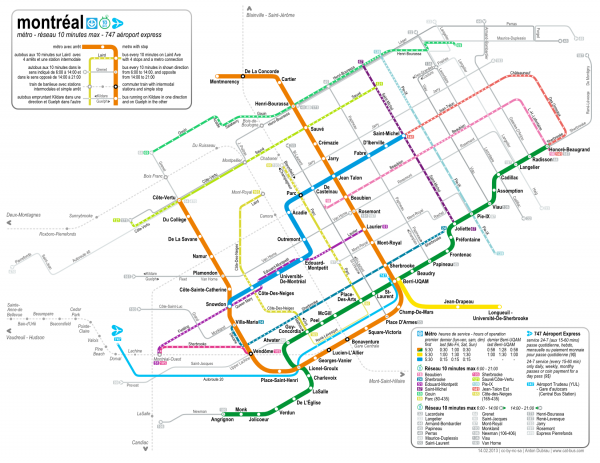

To put this in perspective, at 10K riders per day, the REM airport station would be equivalent to the 57th busiest station of the Montreal Metro, out of 68 stations in total. At 5K riders, it would be on par with Georges-Vanier as the second least used station of the system.

Of course, when you build a Metro line, it makes sense to add stations along the way even if their ridership won’t be that great. But would it make sense to build several kilometers of metro just to reach Georges-Vanier? I think not.

Conclusion & Questions

What we see from all this is that airport connectors, even successful ones, may only attract very few riders per day relative to their cost. We shouldn’t spend a billion dollars to help 5000 people, because on another project, those billion dollars could help 50,000 people.

If we do build an airport connector, it should be as part of a transit project whose main utility is not based on the airport connection. Basically, transit lines should be useful to as many people as possible, and an airport connection can be added if the marginal cost increase is relatively small.

The REM appears, at first glance, to do exactly that. But I still wonder, if I start to dig deeper, will the connection that is made to the airport make sense? Will it be cheap enough to justify building a rapid transit line to a terminus promising such low ridership? Is the airport connection that’s included in the REM project an efficient use of money? Is there a way to be more cost-effective? Is it a good use of public money?