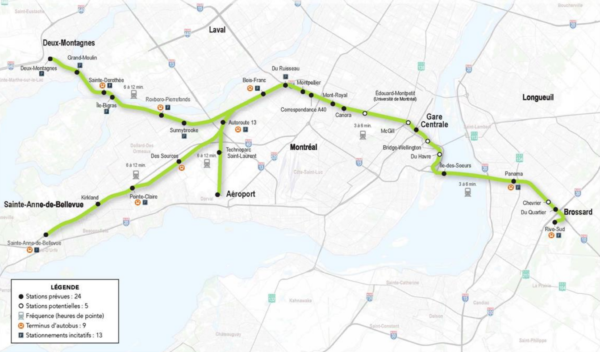

Privatization of the Deux-Montagnes Line:How to Value a Transit Line?

Wednesday, December 20th, 2017

How do you make subsidized transit profitable overnight, without moving a single stone?– By privatizing it, but not in the way you’re thinking.

During the BAPE consultations for the REM last year, I ran into Aref Salem, a city councillor who was a board member of the AMT (now RTM). He was quite in favour of the rail project: his riding is bisected by the Deux-Montagne commuter rail line, which will be replaced by the REM. He was also part of then-mayor Coderre’s administration.

When I expressed concerns about below-value privatization of the infrastructure of the Deux-Montagnes line, including the important Mont-Royal rail tunnel, he assured me: “there will be a detailed accountingâ€.

Well, Quebecers are still waiting for that detailed accounting, which is starting to be urgent, since the project is still rapidly moving forward: in 2 months, the CDPQ hopes to announce the consortium who will build the REM.

How much will the CDPQ pay for the Deux-Montagne line?

CDPQInfra has repeatedly dodged the question of how much they will pay for the line. So far, there has been no clear answer, although they claimed they won’t receive subsidies via the line, and that they will pay “market value†– the market value of an asset being the price that can be obtained on an open and competitive market.

It’s hard not to be cynical about this kind of statement, as there isn’t exactly an open “market†for underground rail tunnels. There also isn’t any competition, for example in the form of a bidding process. Instead, the government has decided to transfer the Deux-Montagnes line to the CDPQ, just like that.

So how much will they pay for the line?

From the few numbers that are available, we know that:

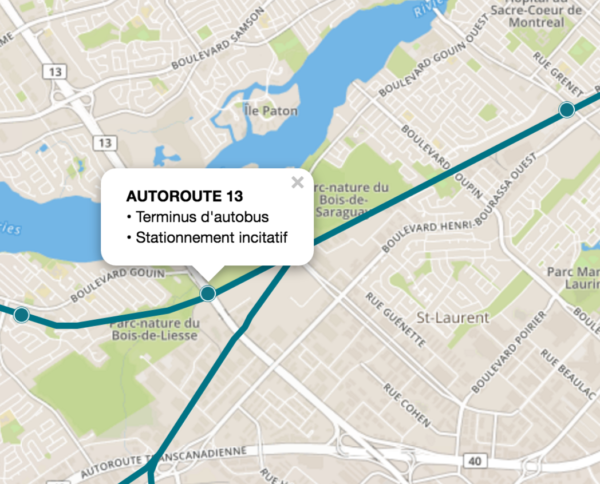

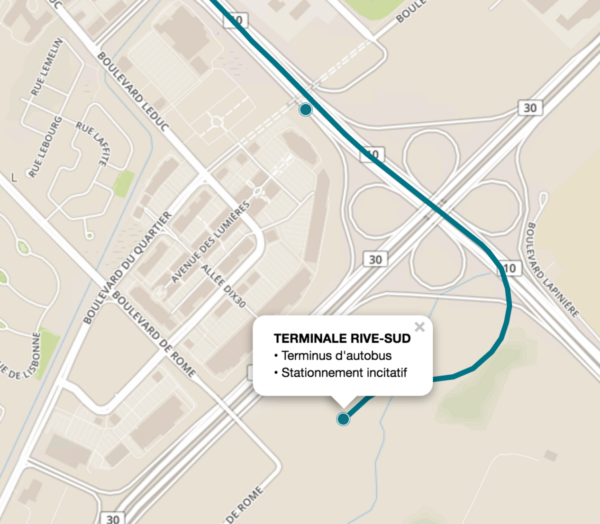

- the CDPQ planned to pay 585M$ for the “acquisition of the corridor†(which includes the line), relocation of utilities and soil decontamination.

- the responsibility for moving utilities and soil decontamination was apparently later shifted to the government of Quebec, which lists it as 180M$ in this budget note (see page 16)

- Which leaves only 400M$ for all land acquisition. But the existing Deux-Montagnes line is only 30km out of the 67km required for the REM, so they can’t have counted more than a couple hundred million to buy it.

Although CDPQInfra hasn’t given explicit numbers on how much they expect to pay, they like to remind us that the AMT bought the line from CN in 2014 for only $97 million. As if to insinuate that the line is really only worth that much.

We’re talking 100M$ for an electrified, rapid transit line that is 30km long, including a 5km tunnel. Am I the only one who thinks that seems just a little bit too low for a line that would surely cost billions to build today?

Yet we keep hearing that number, as if that was all the money we’ve ever put into the line.

Evaluating the actual value of infrastructure is not exactly a straightforward task. In this article, I’ll be looking at:

- How much money did we actually Invest in the line?

- How much is the line worth on the RTM’s Books?

- How much the land of the line is worth?

- Business valuation using dividend discount model

- How the ownership model moves infrastructure out of public control

- The replacement value

- Summary

How Much Money did we actually invest in the line?

It turns out that we’ve invested much more into the rail line over the last decades. Even the original construction of the line and the Mount-Royal tunnel a hundred years ago was actually paid by the public. The tunnel and line were built by the private Canadian Northern Railway, but the Federal government paid for it when the company was nationalized (aka bailed out) in 1918 in exchange for funds to repay construction debts.

Of course it probably doesn’t make sense to count investment from that far back, and the line didn’t see much investment in the 60s, 70s and 80s anyway.

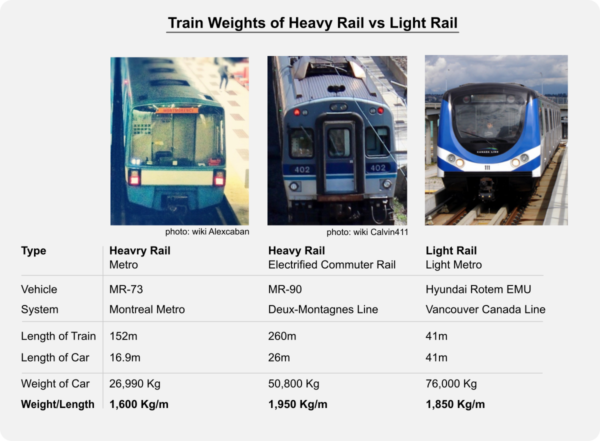

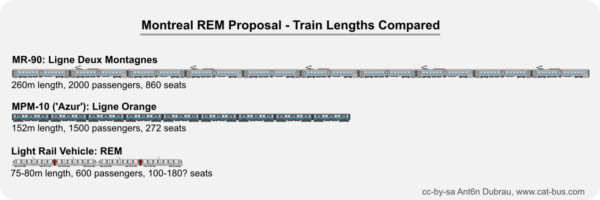

However, there was major renovation starting in 1992. It cost about 300M$ to rebuild the overhead electrification infrastructure and buy new trains. After that, the AMT invested more money, most notably over the last couple of years.

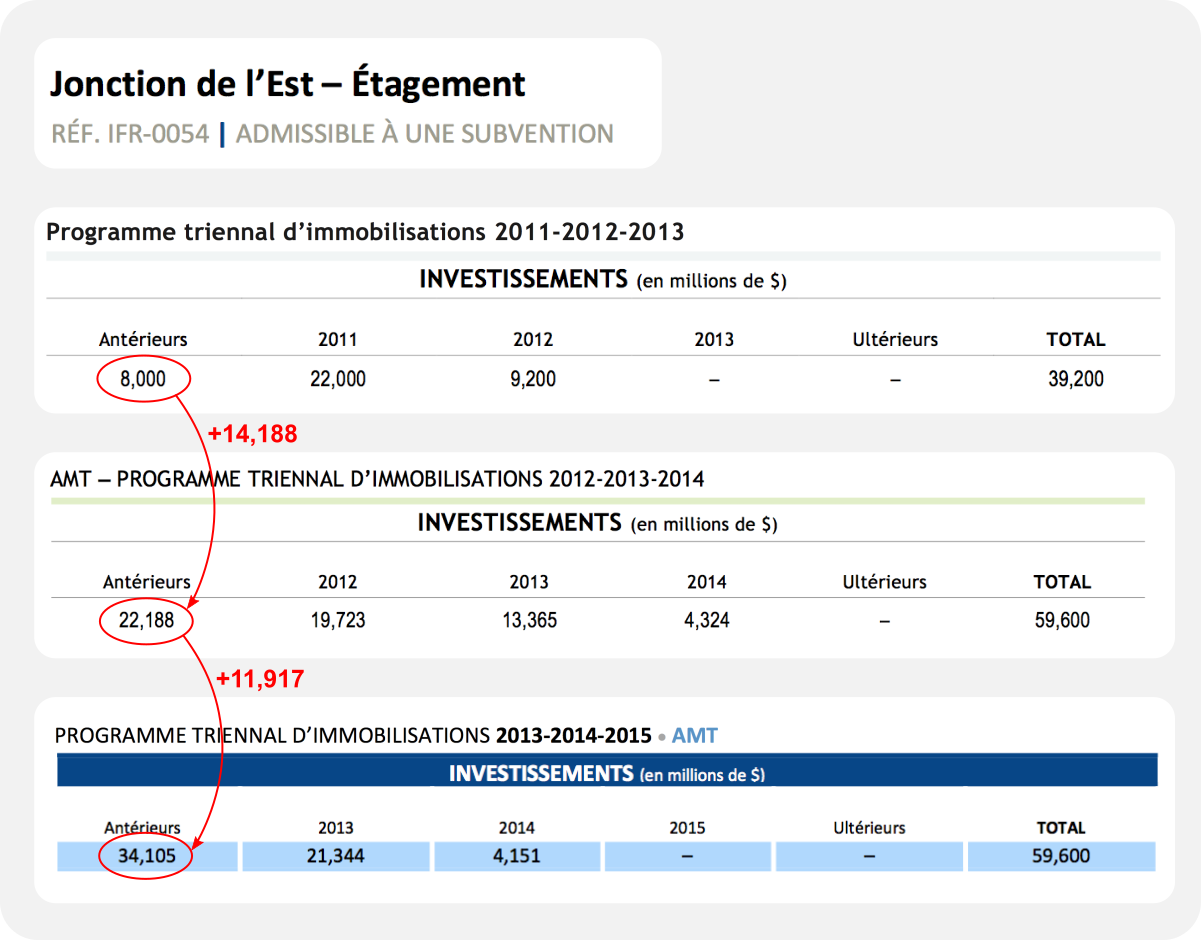

To figure out how much in total, we can look at the three-year capital plans of the AMT. This document is published every year and contains not only a breakdown of funds the AMT hopes to spend on every project in the future, but also the total amounts spent in the past.

By looking at consecutive years and calculating the difference in the total amounts spent, it is possible to figure out how much money was actually spent every year:

Example: some capital plan entries for the Eastern Junction Grade separation project.

In any year, the AMT never really spent as much as they hoped beforehand.

Also, the total estimated budget keeps increasing.

Going through the capital plans since 1996 (I found 20 in total), and tracking every project related to the Deux-Montagnes line, I found that we spent the following:

| Big Projects | 733.3 M$ |

|---|---|

| DM infrastructure rebuild (1993-1995) | 168.0 M$ |

| Trains – MR-90 acquisition (1994-1995) | 130.0 M$ |

| Acquisition from CN (2014) | 97.0 M$ |

| Jonction de l’Est (2011-2015, 100%) | 50.6 M$ |

| Reno Tunnel (2012-2017, 100%) | 43.2 M$ |

| Reno Tunnel (2018-2019, 100%) | 50.2 M$ |

| Centre Entretien P-St-Charles (2008-2017, 60%) | 175.2 M$ |

| Centre Entretien P-St-Charles (2018, 60%) | 19.1 M$ |

| Small Projects | 152.5 M$ |

| Trains – MR-90 improvement projects | 19.7 M$ |

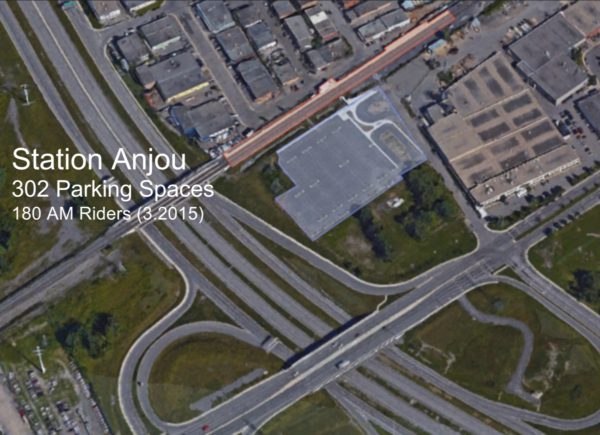

| Parking lots | 11.6 M$ |

| Stations | 3.0 M$ |

| Infrastructure (tracks, signals, overhead,h etc) | 20.2 M$ |

| Studies | 5.3 M$ |

| Other Deux-Montagnes Projects | 1.0 M$ |

| Various Shared Projects | 91.8 M$ |

| TOTAL | 885.8 M$ |

We find that even though we only bought the line 3 years ago for 97M$, the public invested about 886M$ in the line over the last 25 years. Even if we remove the trains (rolling stock) from the calculation (the RTM will likely keep them), that still leaves 736M$ invested [3]. If CDPQInfra takes control of the line, acting like a private entity, shouldn’t they reimburse us for these investments?

But it may not be so easy: The money invested may not ended up on the books of the RTM. Maybe we could check how much these investments are considered to be worth on the books.

How much is the line worth on the Books of the RTM?

When a company invests money into assets, these assets will show up on the balance sheet with their book value. The book value is basically the original cost of the asset, minus amortization. Amortization reduces the book value every year to account for the fact that assets may have a limited useful life (and may eventually become worthless and will need to be replaced).

The AMT has a very basic asset statement in their annual reports, which was broken down by line, but unfortunately only until 2008. Since then the AMT has become more secretive, and I wasn’t succesful trying to get this information via an access-of-information request. Either way, the data we have allows us to get an idea of the book value at least until 2008:

| 1997 | 2002 | 2005 | 2008 | 2017 | |

| Book Value: Trains | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Â Â Â cost | 129.2 M$ | 129.2 M$ | 129.7 M$ | ? | ? |

| Â Â Â amortization | ? | 27.5 M$ | 54.3 M$ | ? | ? |

| Â Â Â net | ? | 105.0 M$ | 75.4 M$ | ? | ? |

| Book Value: Land & Infrastructure | |||||

| Â Â Â cost | 87.6 M$ | 93.9 M$ | 95.5 M$ | 97.1 M$ | ? |

| Â Â Â amortization | ? | 50.8 M$ | 40.4 M$ | 29.9 M$ | ? |

| Â Â Â net | ? | 43.1 M$ | 55.1 M$ | 67.3 M$ | ? |

| Comparison: Land & Infrastructure Investment | |||||

| Investment | 171.0 M$ | 179.7 M$ | 1,837.3 M$ | 209.1 M$ | 666.9 M$ |

We see that the “Cost†of the Book value is lower than the money invested, and the amortization keeps reducing it further. Of the big renovation project in the early 90s, only the trains (about 130M$) ended up on the books in its entirety, whereas only half of the 168M$ infrastructure investment did – and was reduced to only a quarter within ten years by amortization!

By 2008, even though about $200M were invested in the line (excluding trains), the net book value was only about $67M. Since then, there has been much more investment into the infrastructure, and the line (land) was purchased for $97M.

If the book value has continued trailing the invested money as much as it did until 2008, my best guess is that the book value may be somewhere between $200M and $300M, maybe some more.

We see that, even though the AMT invested a lot of money, this is likely not reflected in the book value of the assets. Maybe it’s related to the AMT investing in infrastructure that was owned by CN, a private entity. Since the AMT/RTM isnt’t a private company, and they don’t pay taxes, this doesn’t really matter.

But it does matter when we want to privatize their assets: It is quite possible that the CDPQ hopes to pay exactly this low book value for the Deux-Montagnes line, as the estimates seem somewhat similar. It also matches Aref Salem’s assurance that “there will be a detailed accountingâ€.

A further problem is that the book value is not representative of the market value anyway. The book value is really just a tool used in accounting and taxation. And in the case of the Deux-Montagnes line and the AMT, it seems to be much less than the money we invested.

In general, most businesses are actually worth much more than their book value. This is because in a business, the assets come together to create a more valuable whole, which keeps increasing in value over time as well, whereas the book-value is always going down!

For comparison, utility companies are worth about 3x more than their book value on average, meaning the the Deux-Montagnes line, if considered like a utility company, could be worth $600M – $900M (assuming the book value isn’t an under-estimate).

The raw book value, while higher than the $97 million acquisition, still seems rather low. To see that, let’s compare it to the value of the land alone.

The Land Value

We can actually make a good estimate of the value of the land the line is on. For any building, we can go to the assessment roll, plug in its address (or lot number) and find the municipal valuation. It’s not quite a market valuation, as it is only used for tax purposes, but it gives a pretty good idea. If you’ve ever bought or sold a house, you know that municipal valuation is often much lower than the selling price of the property.

It turns out that almost every piece of land is in the assessment role, including public land.

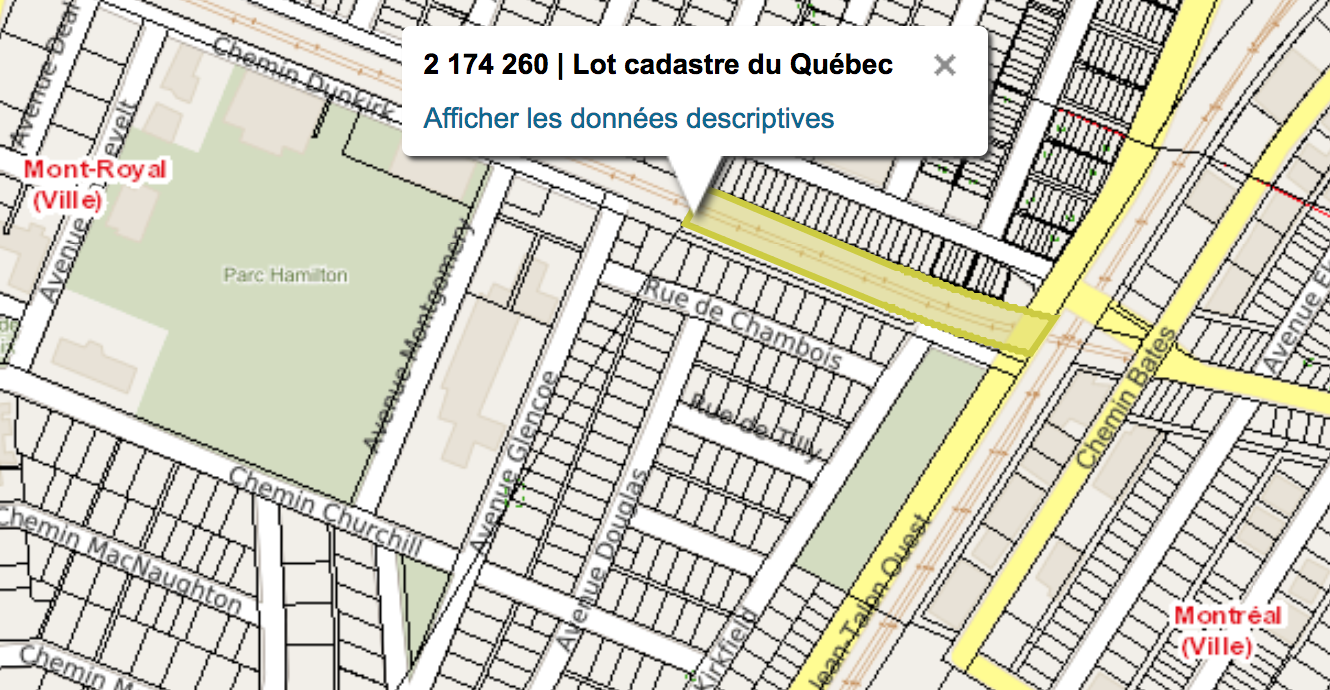

Lots belonging to the Deux-Montagnes line can be found by collecting them with infolot.This image shows the lot just outside of the Northern Mont-Royal Tunnel portal.

I have collected a list of lots belonging to the Deux-Montagnes line in Montreal, Laval, and Deux-Montagnes, and tallied their municipal valuations in a spreadsheet. Here’s the summary:

| Land Valuation – excludes tunnel, infrastructure, rolling stock | |

|---|---|

| Property value | 238,760,007 $ |

| Building value | 2,932,400 $ |

| Land value (property minus building) |

235,827,607 $ |

| Terrain area (square-metres) | 1,149,038 |

| Value per square-metre | 205 $ |

| Number of roll entries | 55 |

The actual value of the Deux-Montagnes line is much higher, since:

- Some lots are valued at only 1$ (maybe because the AMT/RTM doesn’t have to pay taxes anyway).

- The list only includes the lots that I could find, there may be some missing.

- It’s not a market valuation of the land, as previously mentioned.

- The building values (the values of what’s build on top of the land) are very low — which means the valuations effectively only include the value of the land, it doesn’t include the infrastructure (rail + electricity supply + parking lots).

- It doesn’t include the trains, the Mont-Royal tunnel, or the downtown connection.

Even so, the municipal valuation of just the land itself is similar to what I estimated for the book value.

Clearly the market value of the line must be much higher than that, given all the infrastructure that is on it. But how do we make a more rigorous and accurate estimate, based on accounting principles, that’s not just a guess?

Business valuation – the Value of the Contract

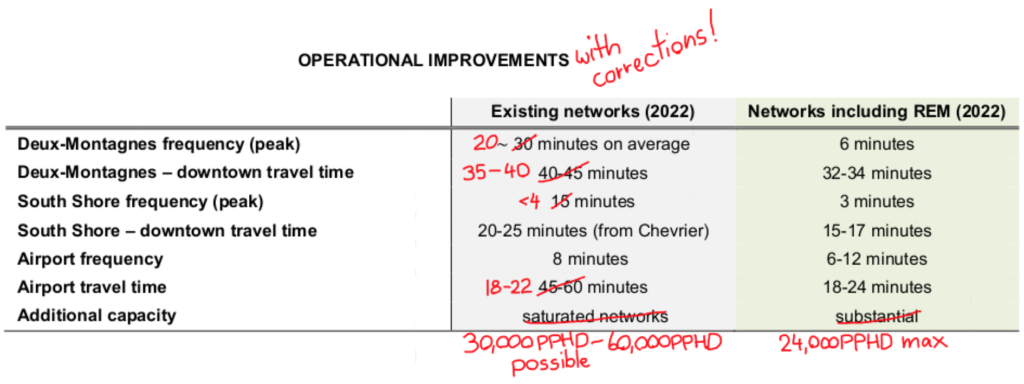

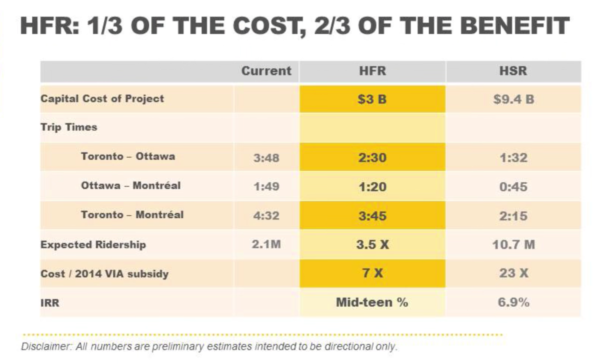

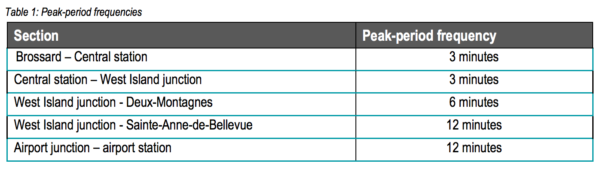

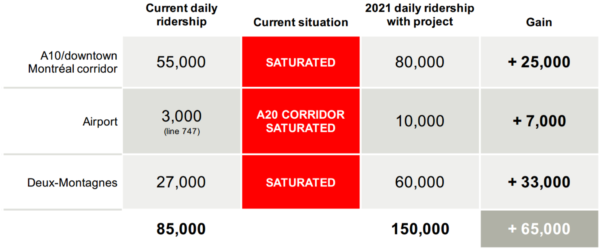

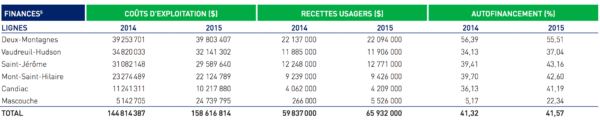

One key element is that the REM is a business. Its goal is to make money by operating the transit line. And unlike what the news have been saying, the profits won’t come from ticket sales, but from the per-passenger subsidy paid by the ATM, which is guaranteed in the contract between the CDPQ and the ARTM.

This is how it works: the ARTM will collect the fares, and pay CDPQ Infra a fixed price of 70 to 71 cents per passenger-kilometre, which is actually more than what it costs to run the line today (30cents)!

People like to think that privatization is a good way to increase cost efficiency, and REM proponents like to suggest that it will be profitable because of automation, but this is simply false. The REM will be profitable because of the Contract, and the subsidies granted by it.

So how do you make subsidized transit profitable overnight, without moving a single stone?

— By privatizing it and over-subsidizing it, and suddenly the subsidies are called “profitsâ€!

If you think about it further, without even building the REM, if the Caisse just keeps running the Deux-Montagnes line as it is run today, the line will suddenly become profitable!

And if you have a bit more imagination, the CDPQ could take ownership of the line, contract the operations back to the RTM and STILL make millions in profit every year without doing anything!

But back to our valuation: the fact that the Deux-Montagnes line will be a profitable business, thanks to the large amounts of subsidies, allows us to use a simple business valuation method usually used for valuing companies on the stock market (i.e. for stock valuation), the dividend discount model.

This method is used for dividend-paying companies, which pay out their profits to shareholders instead of investing into growth, and thus have relatively little growth. The REM fits this category. The idea behind the dividend discount model is that a company is worth the sum of all future dividend payments, adjusted back to their present value.

In simplistic terms, it says if a company pays 5$ in dividends each year, and you believe that a company with that risk profile should yield 5% every year, that the company should be worth 100$ (meaning you will make back your initial investment in 20 years). If there’s an expectation that the dividends will increase, than company should be worth some more.

The valuation will depend on:

- The expected profits

- The expected growth in profits

- The target return rate (i.e. annual return on investment)

The target return rate depends on how risky your investment is: you want more return on more risky investments. As a comparison, bonds, which are one of the safest forms of investment, typically only return 2 to 3%, whereas the overall stock market returns about 5 to 6%. Riskier investments require much higher returns to make financial sense.

In the case of the Deux-Montagnes line, the risk is pretty low. The ridership is already established (based on population) and has been consistent for many years. In fact there’s pent-up demand that the line cannot serve. Furthermore, there’s language in the agreements/laws with the CDPQ that public transit agencies are not allowed to establish competing transit services, which basically grants the REM a cushy monopoly!

In fact the only risk for the line is operational (can we continue operating the line at the current cost without major issues?). It is quite reasonable for a company like that to have a return of 5%-6%. This is also similar to Canadian funds of dividend-paying companies, which have total returns in the 5-6% range (but tend to have higher risks because they are businesses that need to compete with others).

For the growth, let’s just assume there’s no ridership growth whatsoever, and simply assume that income, cost and thus profits will rise with inflation, about 2%.

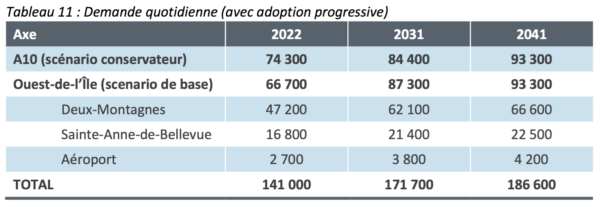

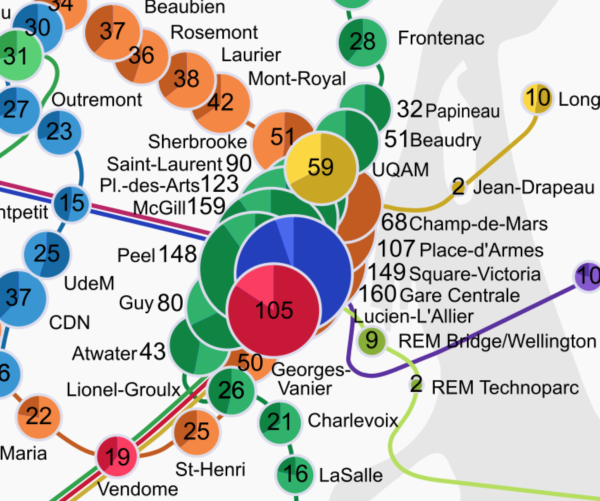

To figure out the profit, we need to deduct the operating cost (30c/passenger-km) and the capital costs from the subsidy per passenger-km (70c/passenger-km), and multiply that by the total number of passenger-km per year (140 million km).

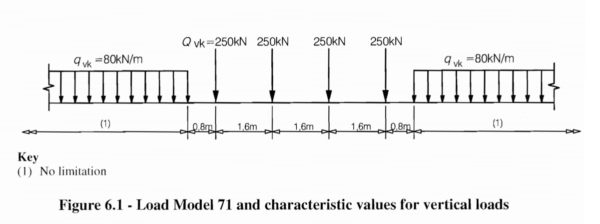

To complete the equation, we need to find the capital costs. During the last 25 years, the public invested about 25M$ per year in the line, mostly for the renovations in the early 90s and further investments in recent years. These were done to significantly increase ridership. If we are only interested in keeping the infrastructure in a good state of repair (and replace the trains every 40 years), we only need 15M$ per year, as a sort of steady-state capital cost.

To go back forth between the cost per passenger-km and the total cost, we simply have to multiply or divide by the total number of annual passenger-km on the line, 140 million km.

| $/passenger-km | total $ | |

|---|---|---|

| operating cost | 0.30 $ | 42,000,000 $ |

| steady-state capital costs | 0.11 $ | 15,000,000 $ |

| revenue (subsidies) | 0.70 $ | 98,000,000 $ |

| profits | 0.29 $ | 41,000,000 $ |

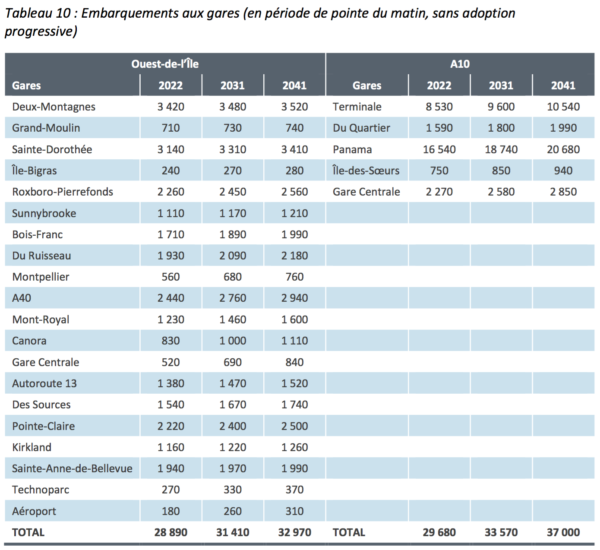

Applying the dividend discount model, we get the following valuations:

| target annual rate of return | 5% | 6% |

|---|---|---|

| profit / year | 41,000,000 $ | 41,000,000 $ |

| profit growth per year | 2% | 2% |

| Valuation | 1,366,666,667 $ | 1,025,000,000 $ |

Business valuation – With some Investment to Increase Ridership

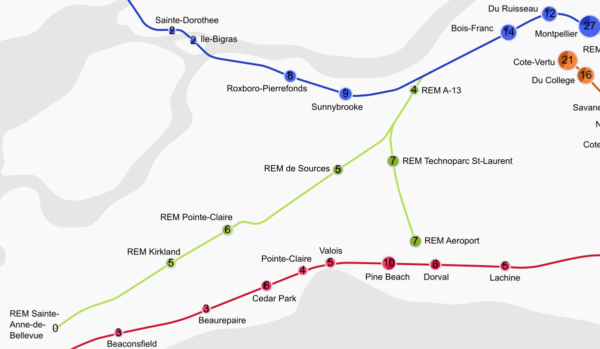

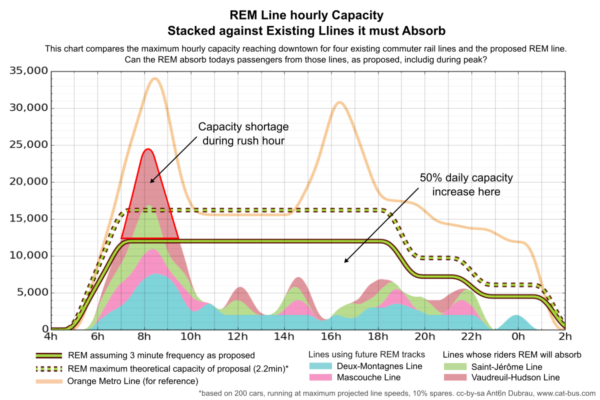

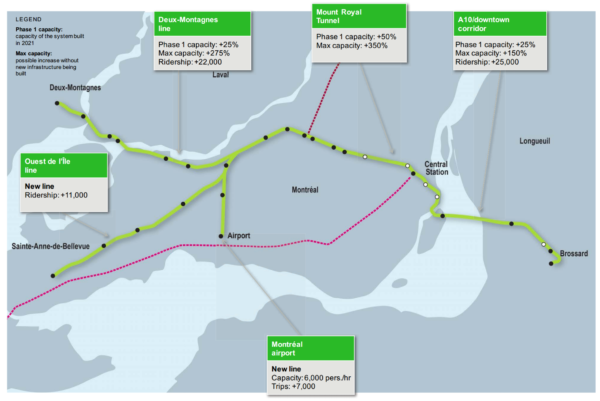

One thing to consider is that there’s a lot of pent up demand on the line that cannot be met because the capacity of the line is too low today. Investments in recent years were aimed at providing more service to catch all that potential ridership, but there’s been no increase in service yet. So even a small additional investment, like 200M$, could get a ridership increase of 25% [1]. This changes the valuation as follows:

| target annual return rate | 5% | 6% |

|---|---|---|

| profit / year | 41,000,000 $ | 41,000,000 $ |

| growth per year | 2% | 2% |

| one-time investment | 200,000,000 $ | 200,000,000 $ |

| one-time ridership growth | 25% | 25% |

| valuation | 1,508,333,333 $ | 1,081,250,000 $ |

This business valuation indicates the Deux-Montagnes line and Mont-Royal tunnel may be worth $1.2B. A transfer to the of the assets to the REM for some hundred(s) of million would then be a subsidy of a cool billion dollars.

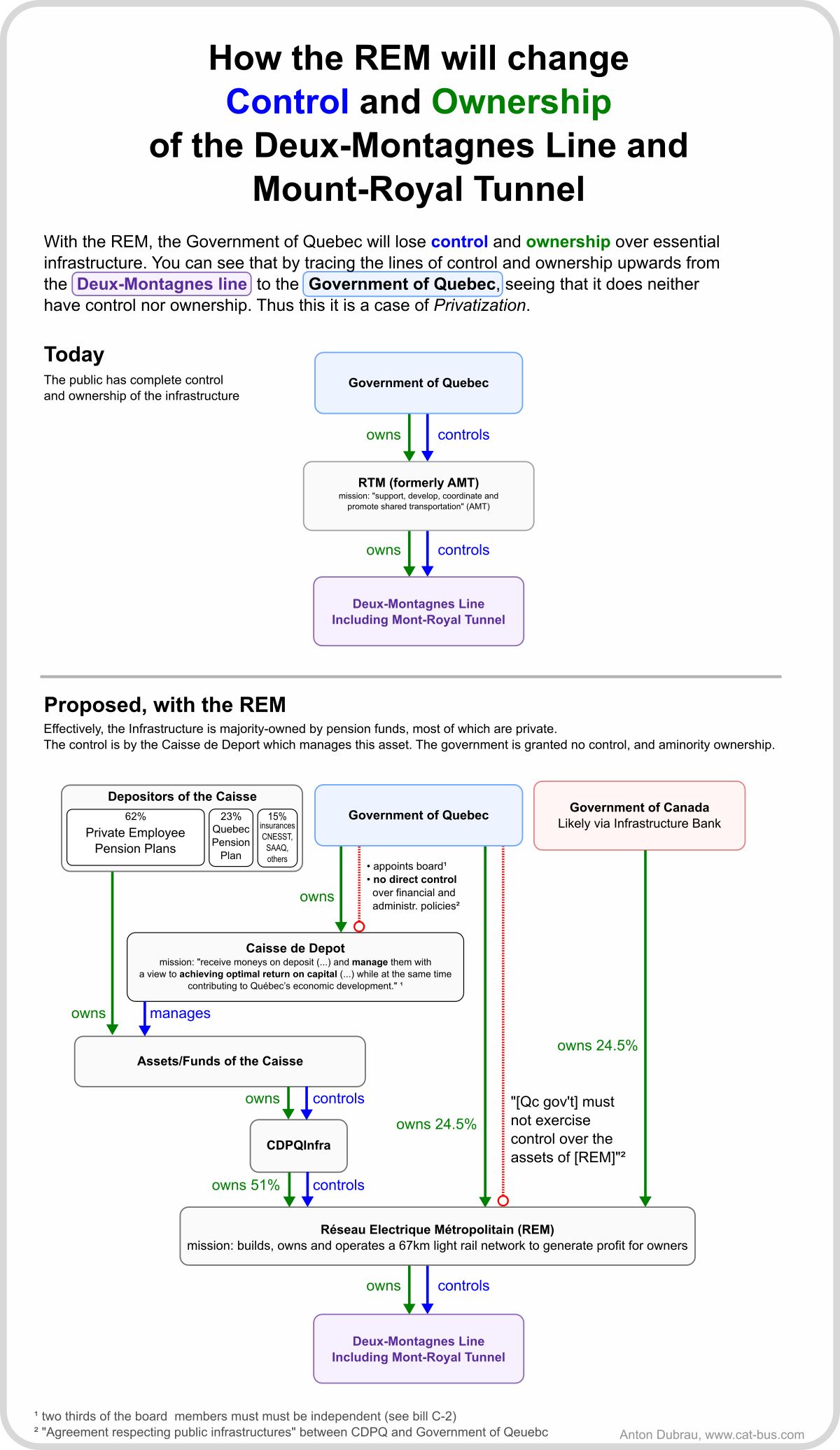

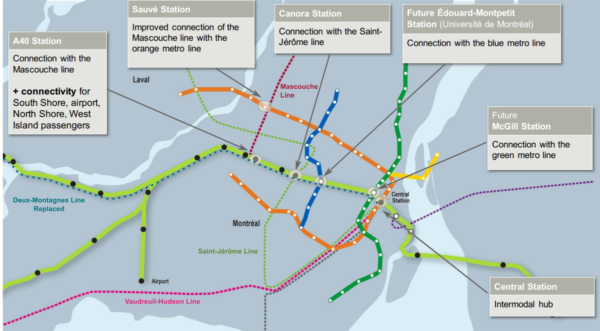

So why should we care? – The Ownership Model of the REM

The REM markets itself as a “public-public partnershipâ€. Since the RTM (former AMT) is a public agency, and the CDPQ is a crown corporation, who cares who owns what. Who cares about subsidies, isn’t it just a case of moving money from the left pocket to the right pocket?

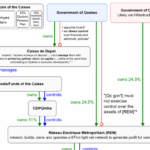

Except… that’s not actually quite true: when the RTM owns the infrastructure, it’s both under control and ownership of the government. Once it’s transferred to the Caisse, it won’t be owned by the public anymore.

Today, if we want to transfer infrastructure between different government agencies, then only the government needs to agree. For example, the AMT built the Laval Metro extension. After it was finished in 2007, the assets were transferred to STM. The government owned the AMT, the government owned the STM [4], deal is done, thank you, goodbye.

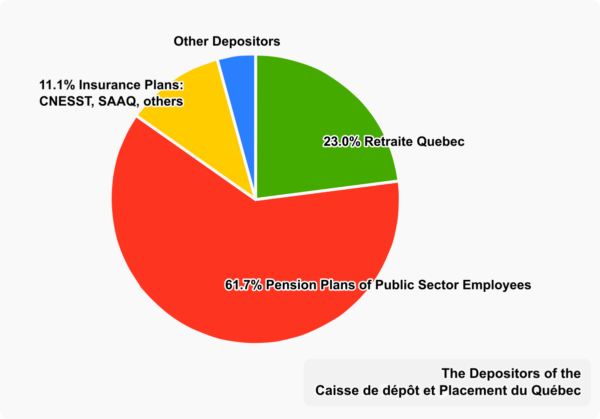

So how is it different if we transfer assets to CDPQInfra? Because CDPQInfra is not owned by the Caisse de Dépôt; it is part of the assets that are managed by the Caisse de Dépôt. And these assets belong to the Caisse’s depositors: Government employees’ pension funds (62%), Retraite Québec/Québec Pension Plan (23%) and others.

It’s the same principle as your personal investments: you have an investment portfolio (RRSP, for example) that is being managed by a financial institution (let’s say Desjardins). Your portfolio may contain shares of Bombardier. Desjardins manages your money, but ultimately you are the owner of these Bombardier shares.

The diagram below shows the ownership structure of the Deux-Montagnes line before and after the REM. As you can see, under the REM, if you start at the Deux-Montagnes line and go up the ownership chain (green arrows), you end up with the Depositors of the Caisse, 62% of which are the pension funds of government employees, and only 23% belong to Québec’s pension plan, the proverbial “bas de laine†everyone talks about.

But ownership is only half the story, and if this was the only problem, I would have given up a long time ago and just accepted that we’re making a very strange deal.

The real problem, the bigger problem, for anyone who cares about the future of transit in Montréal and mobility in the whole province, is control of our infrastructure.

If you go up the control/management chain (blue lines) in the chart above, you see that it ends at the Caisse de Dépôt. Moreover, the Government of Québec explicitly states that it gives up all control to the Caisse.

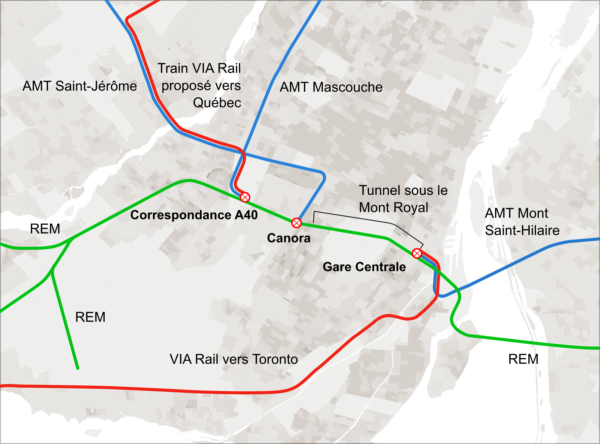

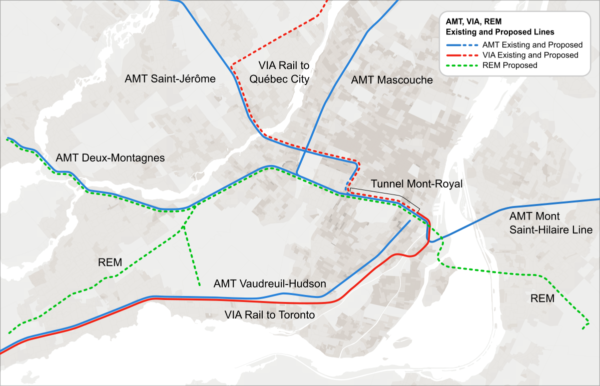

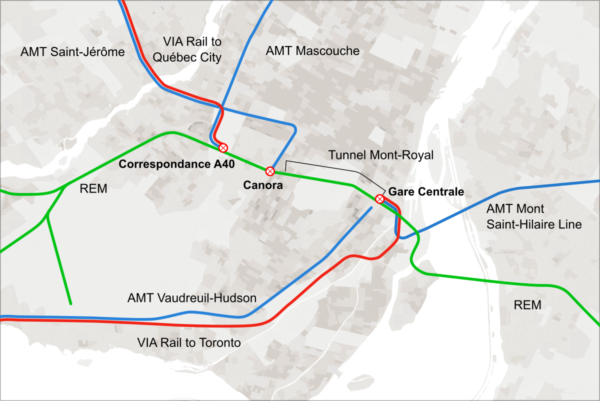

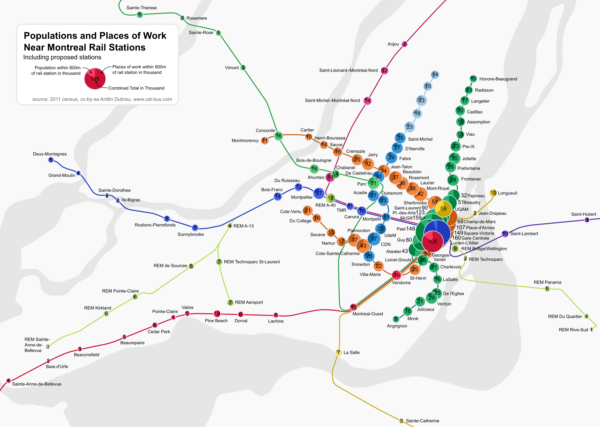

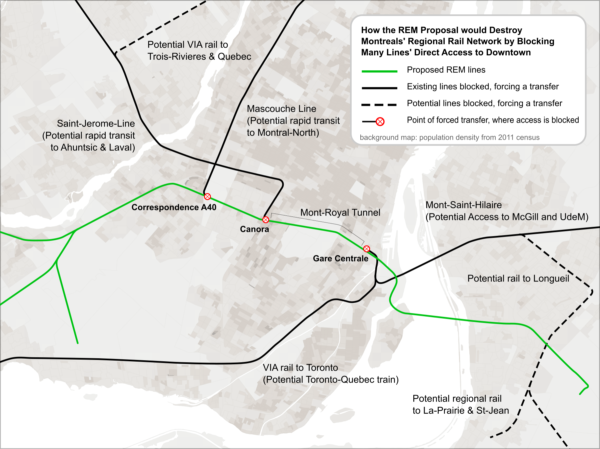

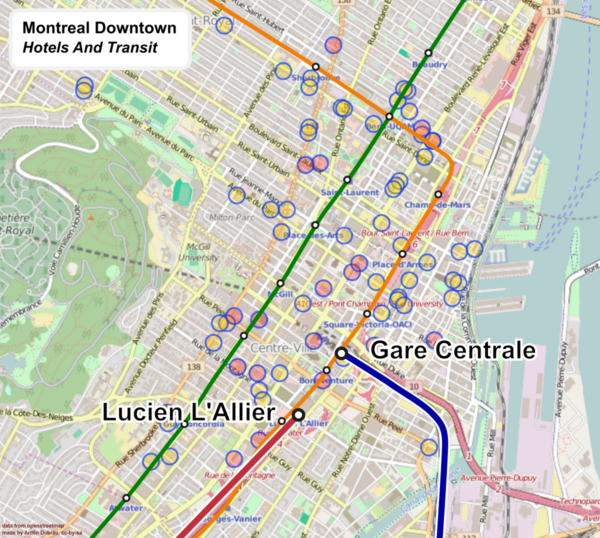

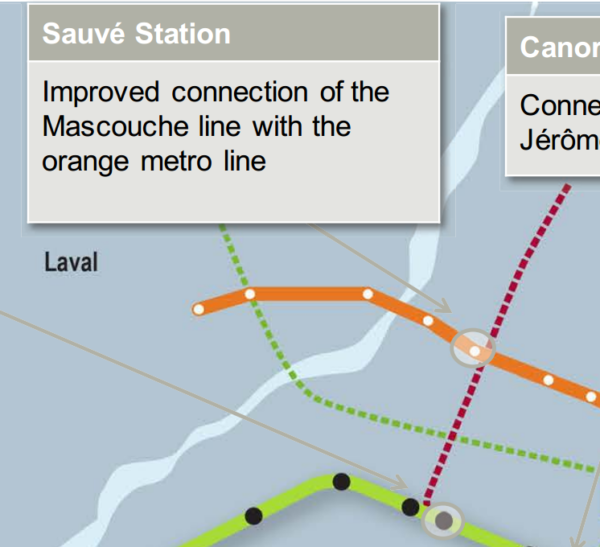

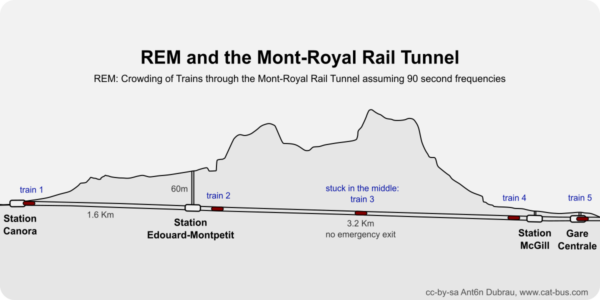

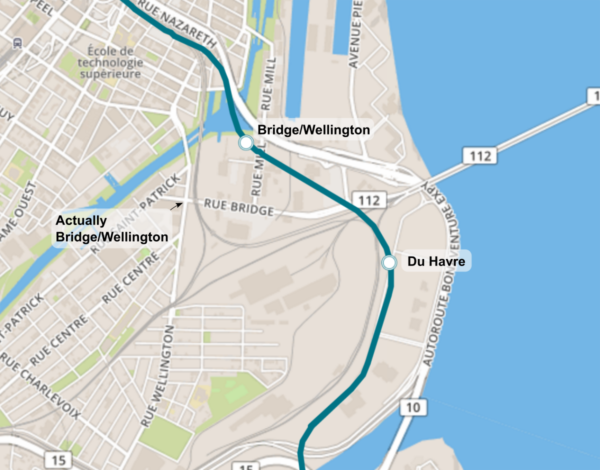

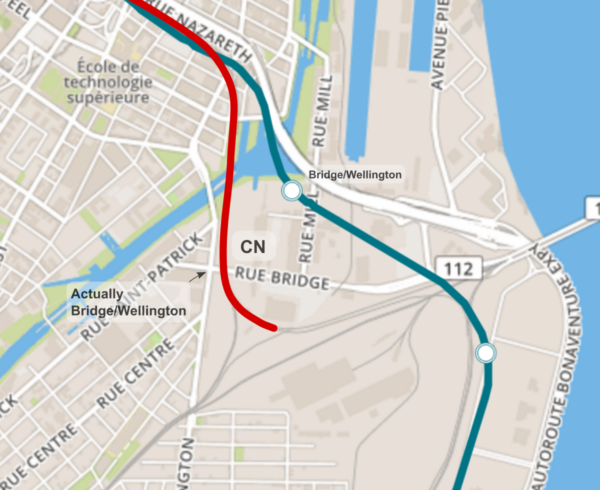

Losing control of the infrastructure means losing the ability to determine how it will be used: The Deux-Montagnes line includes the Mont-Royal tunnel, which many transit lines need to use to reach downtown. But after privatization, the line will not only have a lower capacity, but half the lines that need to use it will be cut off from direct access downtown, maybe forever.

Also, while in the rest of the world, public-private partnerships have private corporations build new infrastructure that are eventually given back to the public, our innovative public-public partnership privatizes already-built public infrastructure, without reverting back to the public, and with no chance of ever getting it back.

Transferring it back under public control would effectively expropriate the pension funds who own the assets, while breaking contracts and laws in the process. Essentially, getting our transit line back may require an act of communism.

Of course we could maybe buy it back from the Caisse… I wonder how much they charge for a 30-km line with 5 km of tunnel, which happens to be the only access to downtown Montreal? When the government must negotiate at arms length, and has very little leverage. Do you think they’d let it go for $100M?

But maybe I’m concerned for nothing. After all, I’ve raised the issue with politicians and other proponents of the REM, and the attitude I’m getting is a dismissive “we’ll just build another tunnelâ€. Piece of cake.

This brings up a new kind of valuation — how much would the Deux-Montagnes line cost if we built it from scratch?

Replacement Value

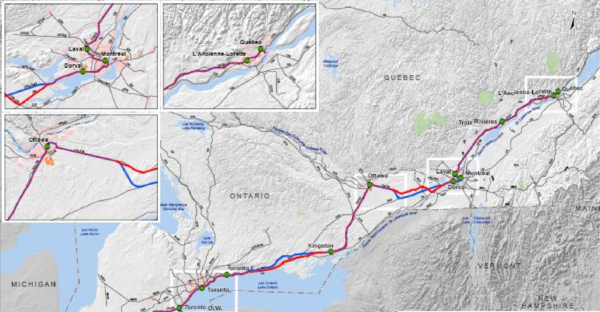

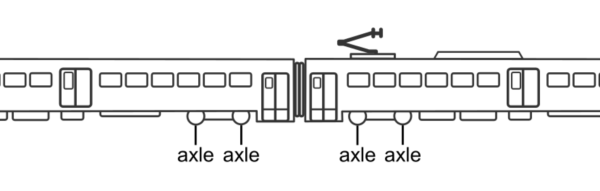

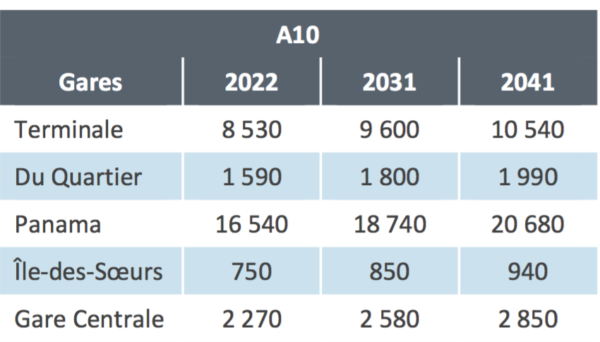

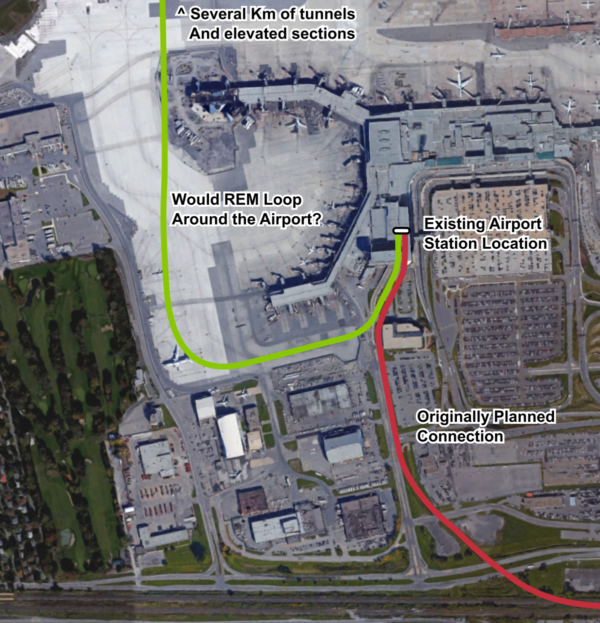

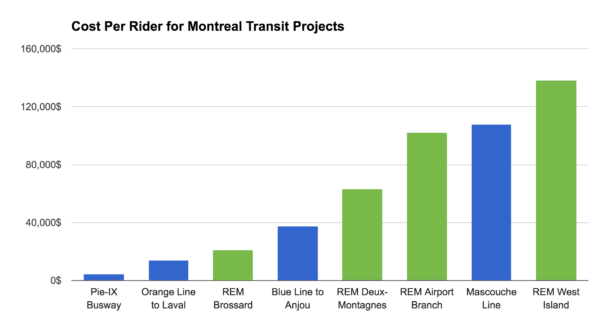

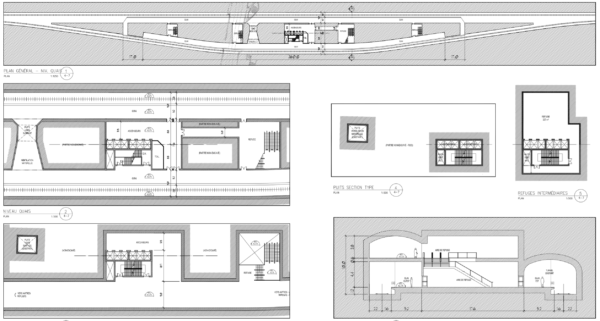

To get an idea how much the line would cost as a hole, we can make a simple comparative analysis. We can break down the line into the surface section (25km) and the tunnel section (5km), and make an estimate by comparing to various per-km costs.

We could compare the Mount-Royal tunnel to various other comparable, recently built rail tunnels (ones with no stations inside the tunnels), but this will not account for the downtown connection. A lot of the value of the Mount-Royal tunnel is the fact that it directly connects to Gare Centrale.

If we built a new tunnel, it would be very difficult to make a new connection to Gare Centrale — there are buildings in the way! Plus, the REM will use up a lot of space of the station.

This means we’d either have very complicated and very expensive construction to make the connection; we could purchase expensive buildings and tear them down; or build a new underground central station. Either way it’s going to be very expensive. This is where a lot of the cost of a new Mount-Royal tunnel would come from.

| Deux-Montagnes Line Replacement Cost | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| item | cost | length | item cost |

| 25km of surface rail | 70 M$/km | 25km | 1,875 M$ |

| 5km Mont Royal Tunnel | 140 M$/km | 5.4km | 756 M$ |

| Downtown tunnel Station / Access | 350 M$ | – | 350 M$ |

| TOTAL | 2,981 M$ | ||

We see the Mont-Royal tunnel adds up to a cool billion, and the surface part to almost two. The Mont-Royal tunnel is the most likely part that will need replacing, and again we’re coming up with a billion dollar figure.

Summary

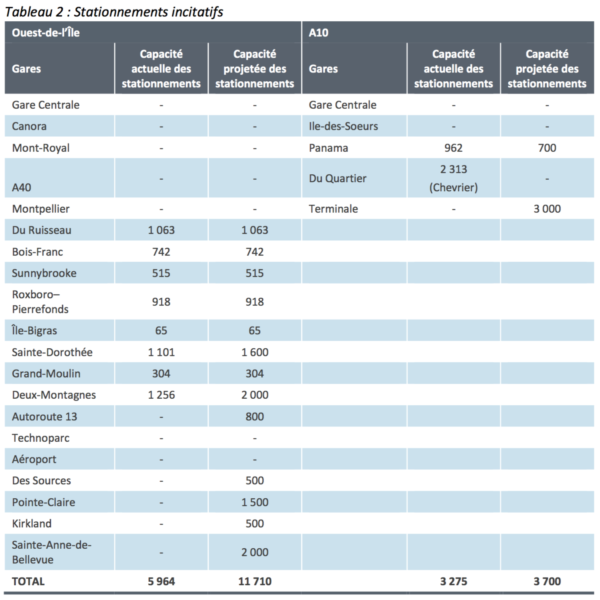

We’ve looked at various ways to grasp the value of the Deux-Montagnes line and Mont-Royal tunnel, and made a comparison to how much CDPQInfra will pay to privatize it.

| type of valuation | valuation amount (M$) |

|---|---|

| What CDPQ may pay | 100-200? |

| Book Value Note: estimate based on continuing 2008 book value |

200-300? |

| Municipal assessment of Land

Note: excludes tunnel, infrastructure, downtown access, parking, trains – and it’s a below-market, municipal valuation

|

236 |

| Total Investment excluding trains | 736 |

| Total Investment including trains | 886 |

| Business Valuation (dividend discount model) | 1000-1400 |

| Business Valuation assuming small improvement | 1100-1500 |

| Replacement Value of whole line | 3000 |

| Replacement Value of Mont-Royal Tunnel only | 1100 |

In my opinion, we should get reimbursed about a billion dollars, maybe a bit more, in exchange for transferring the assets of the transit line, losing control of the infrastructure forever, and giving CDPQinfra an operating contract that would make them profit from day one. Anything else would be a large subsidy, and completely inappropriate to give, without bidding process, to a company acting like a private, commercial entity.

The Deux-Montagnes line is an essential puzzle piece in the creative accounting at work that will create a profitable transit line owned by a private entity — and I worry the public will be “taken for a ride”.

Footnotes

[1] The estimate that 200M$ investment will allow a 25% ridership increase comes from the 2005 annual report of the AMT.

“An estimated $173.9 million is recommended to increase the line’s capacity in order to accommodate the ridership estimated at over 40,000 passengers a day. The work includes the grade separation of the East junction, double railway tracks between Bois-Franc and Roxboro, the addition of two stations and the purchase of 22 new cars.â€

Note the current ridership is 30,000 passengers per day.

The Eastern junction project was completed (for about 60M$), the 22 rail-cars where purchased but allocated to different rail lines, the double tracking is still outstanding. It’s reasonable to assume that the double-tracking and purchase of new rail cars will now cost 200M$.

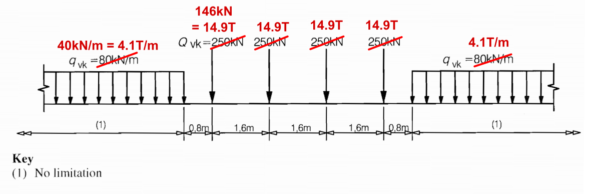

[2] To arrive at the estimate of 70 M$/km for surface rail construction and 120 M$/km for tunnel construction (for a tunnel without stations), I used the following comparative projects:

| Comparative tunnel costs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| project | length | location | opening year | cost | inflation- adjusted in CAD | cost per km (CAD) | |

| Mount-Royal tunnel | 5.0km | Montreal | 1918 | 10 M$ | 145M | 29 M$ | |

| 2nd Hudson-Tunnel | 3.7km | New York | 2026? | 11.1B USD | 14.3B | 3,865 M$ | |

| Barcelona AVE tunnel | 5.8km | Barcelona | 2013 | 179.3M€ | 277M | 48 M$ | |

| East Side Access, only Manhattan tunnel contracts | 3.8km | New York | 2023 | 415M USD | 535M | 141 M$ | |

| Crossrail, only tunnel contracts | 21km | London | 2019 | 1.5B £ | 2.6B | 124 M$ | |

| Fildertunnel | 9.5km | Stuttgart | 2021 | 754M€ | 1142M | 120 M$ | |

| Tunnel Obertürkheim | 5.7km | Stuttgart | 2021 | 350M€ | 530M | 93 M$ | |

| Comparative Surface costs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| project | length | location | opening year | cost | inflation- adjusted in CAD | cost per km (CAD) | |

| Eagle PPP electric surface commuter rail (A-line) | 54.7km | Denver | 2016 | 2.2B USD | 2.83B CAD | 52 M$ | |

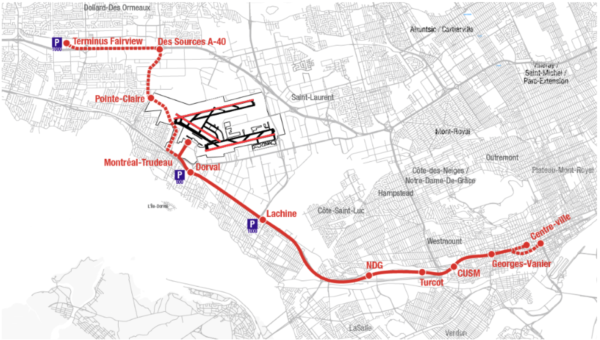

| REM St-Anne Branch | 16.8km | Montreal | 2021? | 1400M CAD | 1400M CAD | 83 M$ | |

| REM Rive-Sud (includes tunnel) | 15km | Montreal | 2021? | 1730M CAD | 1730M CAD | 115 M$ | |

In order to calculate the costs of the individual branches of the REM, I distributed the the estimated construction costs from this document as follows:

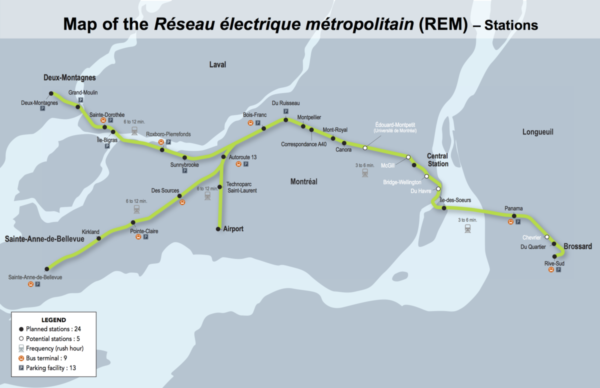

| REM Branches Breakdown | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| branch | length km | infra-structure cost | system & rolling stock cost | parking / terminus cost | acquisition cost (approx.) | total cost |

| St-Anne-de-Bellevue Branch | 17 km | 680 M$ | 446 M$ | 125 M$ | 147 M$ | 1 398 M$ |

| Deux-Montagnes line incl. tunnel (upgrades) | 31 km | 820 M$ | 810 M$ | – | 266 M$ | 1 897 M$ |

| South-Shore Branch | 15 km | 1 090 M$ | 399 M$ | 110 M$ | 131 M$ | 1 729 M$ |

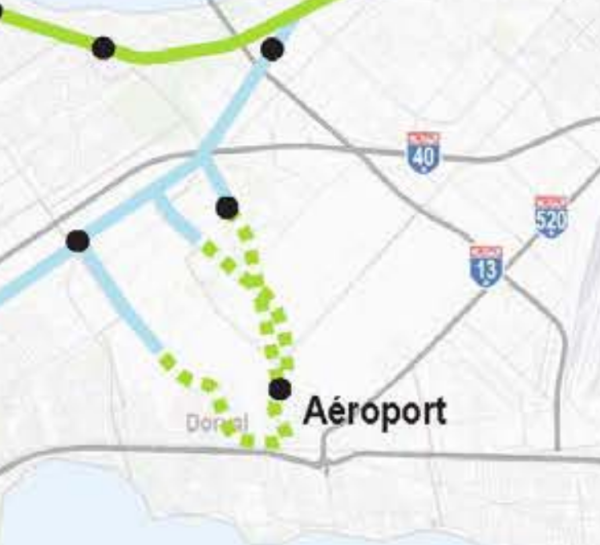

| Airport Branch | 5 km | 320 M$ | 125 M$ | – | 41 M$ | 486 M$ |

| Â TOTAL | 67 km | 2 910 M$ | 1 780 M$ | 235 M$ | 585 M$ | 5 510 M$ |

[3] 885.8M$ (total) – 130M$ (MR-90 acquisition) – 19.7M$ (MR-90 improvements) = 736M$