Ottawa’s O‑Train (Part I): a Little German Train in Canada

Friday, March 29th, 2013One a recent(ish) visit to Ottawa I got to visit one of it’s major attractions – the Ottawa O-Train! I had read about it before, a small project that transformed a short stretch of a freight railway into a transit line, using “Talent” Diesel Multiple Unit trains built by Bombardier. Using these trains is unusual in North America, because they do not fulfil the requirements of main line trains with respect to buff strength (basically they are too light). Although these trains are considered main line trains in Europe, in North America they are called “light rail”. The three Talents that OC Transpo uses for the O-Train were acquired out of an order by DB (Deutsche Bahn), which uses these trains on un-electrified regional rail lines.

The interior of the O-Train should look familiar to people who have taken DB Regio trains. Note how the luggage racks were blocked off.

The arriving train came in a familiar color – the color scheme of DB and OC Transpo are so similar that the trains weren’t even repainted. The interior of the train felt strangely familiar as well, because it is all just the DB design. Having ridden many trains in Germany, I felt like I was sitting in piece of Europe in Canada. The ride is also unusally smooth by North American standards (I haven’t encountered too many rail vehicles with air suspension here).

If you like rail and transit, it’s easy to be a fan of the O-Train. But the real innovation of the O-Train is not the specific train that is used, but the transit planning of the line. It is easy to focus on a particular transit technology (in this case the DMUs), and overlook the transit line that is built with it. And some of of that planning was imported from Europe just like the trains themselves.

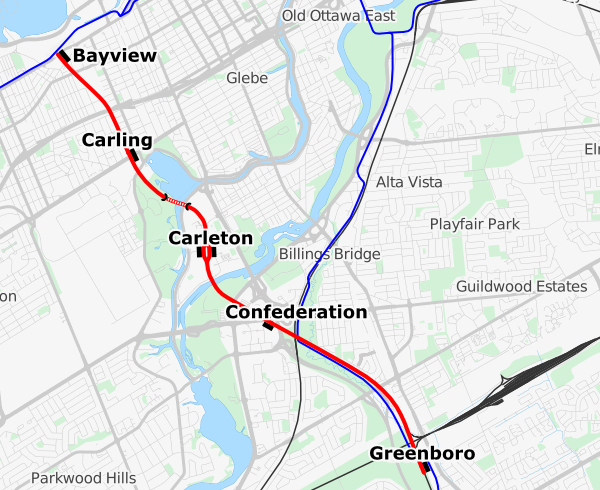

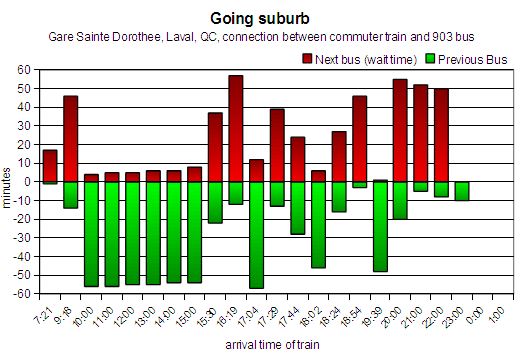

The O-Train is a short line established on a segment of an existing, infrequently used freight line corridor. Along it’s 7.8km length there are 5 stations. At both terminals passengers can transfer to busways. The station at the center, Carleton, provides access to the University, which is otherwise awkward to reach. The line is single tracked, except for the Carleton station, which has two tracks and two platforms. This allows two trains to run simultaneously, passing each other there. The trains take about 12 minutes to traverse the length of the line, and with a short turn-around time, this allows service with a headway of exactly 15 minutes.

One train every fifteen minutes doesn’t sound very often by rapid transit standards, but one has to consider that the schedule is completely regular, the same every hour. The train leaves at :00, :15, :30, :45 and arrives twelve minutes later. This fixed interval schedule (or “Takftfahrplan” in the original German) allows people to easily remember the complete schedule, making the service more convenient even for less than regular riders.

Another way in which the O-Train is more part of the transit network rather than a railroad in the traditional sense is the ticketing. Unlike many commuter railroads, the tickets are integrated with the surrounding rapid transit system, monthly passes are accepted, as well as day passes and transfers from buses. The line is viewed as part of the overall transit network, not some premium service. There are also no conductors aboard, and no turn-stiles either – the tickets are checked randomly, and there’s a fine for traveling without a valid ticket. This system, called Proof-of-Purchase (POP) is heavily used in Europe. It allows operation of the train with the vehicle operator only, no conductors required.

The 35m long platforms at the stations are level with the train entries. There are no steps into the train, and the doors are wide. Not only does this mean the train is easily accessible, it reduces the boarding and alighting time. Together with the reasonably fast acceleration of the DMUs (for example compared to diesel locomotive hauled trains), the resulting short dwell time allows the quick running time which again results in the relatively frequent schedule using only two trains.

The O-train started service in October 2001 as a pilot project to evaluate the Light Rail technologies for Ottawa. Although the specific technology was not chosen for other rail lines in Ottawa (the Confederation line will use electrified low floor LRTs), the line itself has earned its keep. After the first year, the ridership reached around 6200 passengers per day, 9500 by Fall 2004 and close to 14000 by September 2011. A 2005 report, updated in 2008 (pdf, also includes some of the ridership numbers) noted that in 2007, discontinuing the O-train would have required the purchase of 16 extra buses at more than 7$ million.

Note, however, that the cost to revenue ratio for the O-train is worse than for buses: about 26% in 2002, and 36% by 2007, compared to about 55% for the system as a whole. So while the O-train provides a smoother and more comfortable ride, the ticket revenues of the train cover less of the operating expenses than for buses. It shows that rail, even a system as cost-effective as the O-train, needs good ridership and a decent size before it makes economical sense over buses.

There is now a project underway to increase service on the O-train, which is partly done to mitigate the disruption of the transitways while the Confederation Line is under construction. This summer, OC Transpo will shut down the O-train for 18 weeks to allow the construction of two extra sidings (and some other general maintenance). The purchase of 6 Alstom Lint trains back in 2001 2011 will then allow doubling the frequency of trains to every 8 minutes starting in 2014.

Continue on to part II: Ottawa’s O-train – a cost-effective project.